Headline

Few objects are as permanent in the fabric of American culture as the piano. Originally produced on commission for wealthy families in the early 1800s, the piano as an object of material heritage came of age in the first era of mass industrialization. Successive waves of increased efficiency and low-cost immigrant labor gradually reduced the price from a luxury status symbol that could cost as much as a small house to a mass-market commodity that symbolized ascent into the middle class in the post-war era. Despite a precipitous decline in ownership from one piano in every 316 homes in 1978 to less than 1 in 3,000 today, many of the instruments that do survive remain in use, having outlasted their original owners, their makers, the factories they were produced in, and the showrooms where they were sold, still retaining their power as symbols of technology and class mobility.

While Boston, Chicago, and New York would later become the dominant centers of piano making in the United States, Philadelphia was the instrument’s first port of harbor out of Europe, boasting 80 piano makers within the city’s limits in the early 19th century. Artisans Christian Frederick Lewis Albrecht, a German immigrant, and Thomas Loud Evenden, an emigré from London, led the nascent industry in production of high-end instruments for wealthy clientele. Albrecht set up a workshop at 475-77 N. 5th Street and 480-90 York Avenue. He later opened a showroom at 46 N. 3rd Street. Evenden, whose firm Loud & Brothers by 1824 was producing an extraordinary 680 pianos a year, chose to locate nearby at 150 Chestnut Street.

Headline

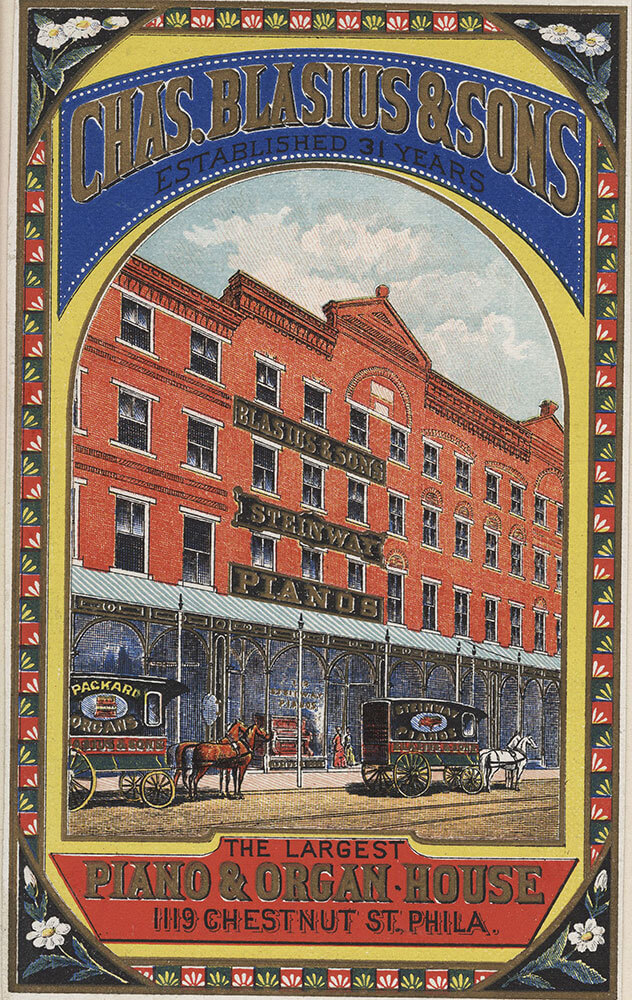

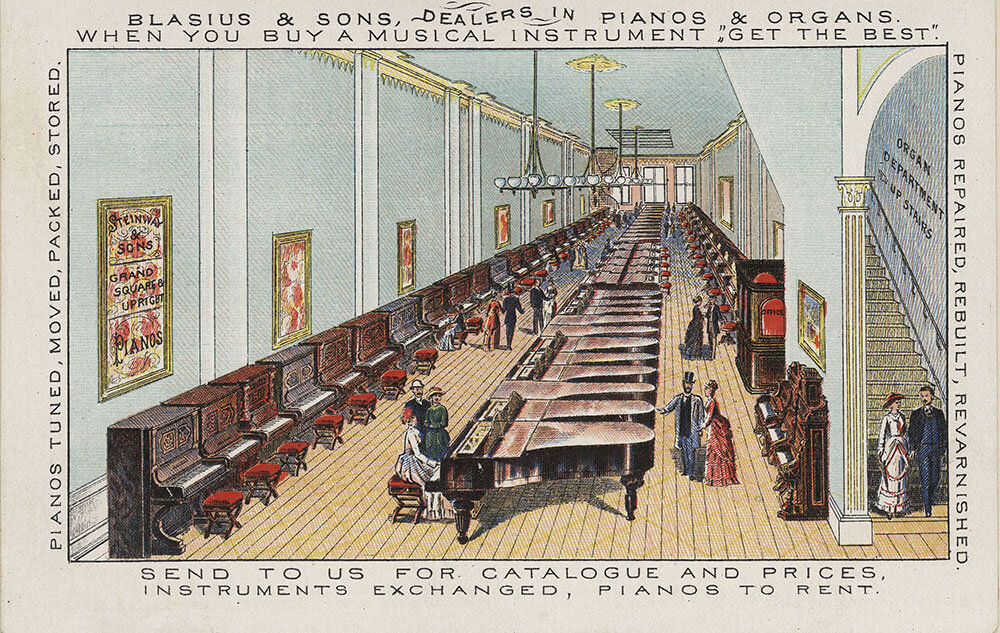

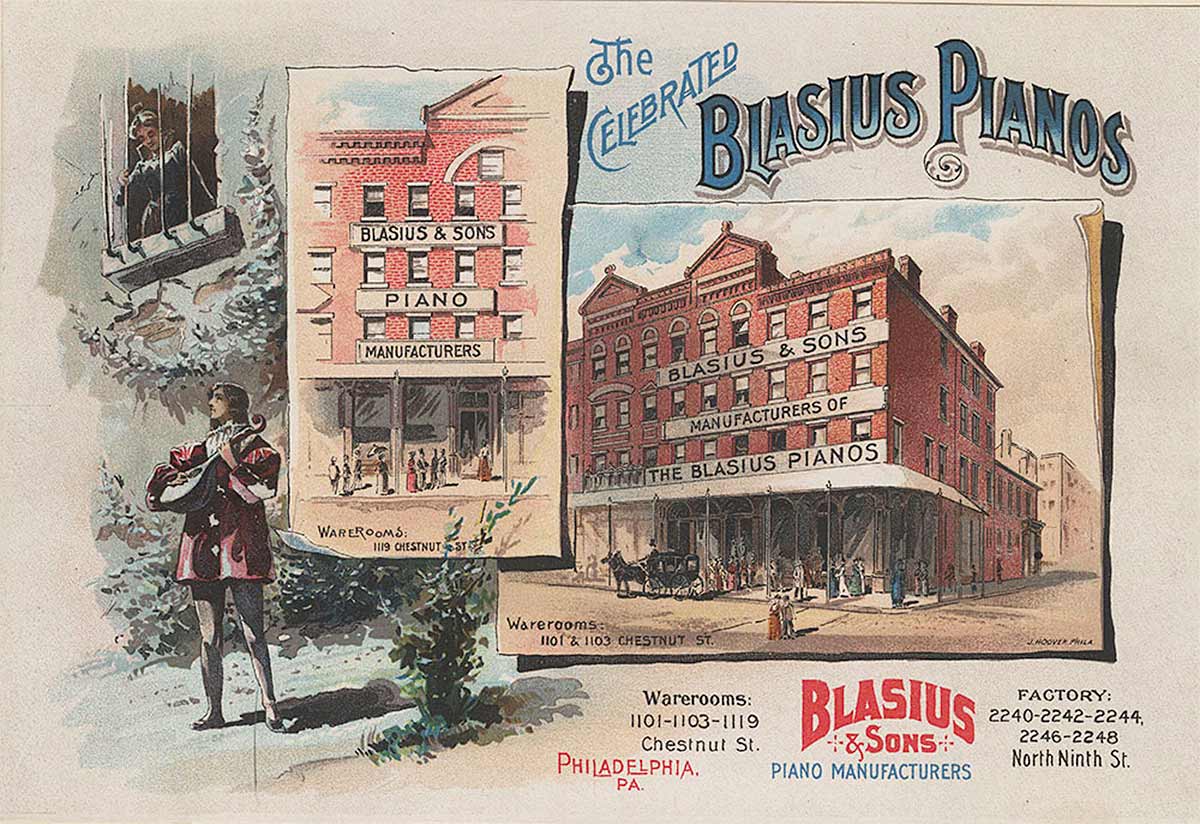

As the city boomed after the Civil War, so too boomed the fortunes of Philadelphia’s piano makers. On Chestnut Street between 9th and 13th Streets, manufacturers began to occupy significant street frontage on what would later become known as “Piano Row,” mirroring the neighborhood’s Jeweler’s Row. Newcomer Charles Blasius, having apprenticed in piano making and established his business in Trenton, New Jersey, moved to Philadelphia in 1857, opening an enormous showroom at 1119 Chestnut Street that advertised itself as “the largest piano & organ house” in the city, featuring prominently for sale Steinway & Sons pianos brought down from New York City. In 1887, as his company’s fortunes grew, Blasius & Sons swallowed Albrecht & Company in an acquisition, expanding the piano seller’s market share.

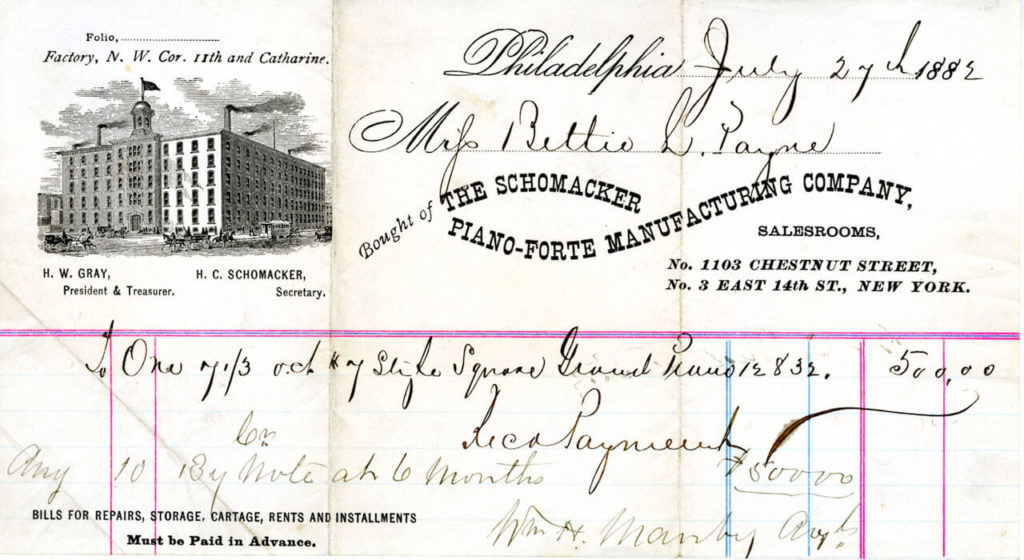

As advances in manufacturing steadily lowered the cost of making pianos, the industry began to shift away from small-batch production for wealthy clientele towards large-scale production for the mass market. Small workshops gave way to large factories on the outskirts of the expanding city. The Schomacker Piano Company, acquired in 1899 by the Wanamaker Department Store, opened a five-story factory at the northwest corner of 11th and Catharine Streets in Bella Vista. In West Philadelphia, Irish immigrant Patrick Cunningham built a seven-story factory at 50th Street and Parkside Avenue (still standing today), adjacent a neighborhood of stately townhouses set across from the idyllic site of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. The Lester Piano Company, the manufacturer with the most pianos extant today, set up a factory in Lester, Pennsylvania and a showroom in Philadelphia on Piano Row.

Headline

Piano makers of this era competed to produce instruments with the most sonorous tone, often claiming their instruments contained the expressive range of an entire orchestra. The marketing hype occasionally backfired. By the outset of the 20th century, year-over-year advancements had yielded instruments which even today possess an astonishing character and warmth of tone, developed through a century of experimentation in woodworking, machining, and metallurgy.

Like all booms, the good times didn’t last. The crash of 1929 and subsequent economic depression were devastating for the piano industry. Demand for luxury instruments fell significantly, and most firms went out of business, unable to adapt to the changing market. Manufacturers like Cunningham Piano Company, which had just completed an 11-story flagship building on Chestnut Street, flailed for a few years before going under and selling off all assets, including the Cunningham brand name.

The few manufacturers that did survive managed to do so by shifting production away from large, high-end instruments to smaller, cheaper to produce mass-market pianos. The Lester Piano Company was one of the few success stories of the Great Depression, able to pivot to manufacturing and marketing en masse their small, cheaply-made Betsy Ross spinets. It is to the chagrin of local piano tuners that so many of these instruments survive today.

Headline

Having never having managed to produce a piano as iconic as Cincinnati’s Baldwin, Boston’s Mason & Hamlin, or New York’s Steinway, Philadelphia largely passed out of renown as a center of piano making. The Lester Piano Company and Wanamaker’s Schomaker brand were the last holdouts, both ceasing production in the 1960s.

Of the original stores that made up Piano Row, none survive today. Jacobs Music, which in 1937 may have been the last retailer to open a new showroom in the city, managed to remain in business largely due to their contract as the area’s sole distributor of Steinway & Sons pianos. The business still operates a small showroom on Chestnut Street, albeit in Rittenhouse Square, which is further west than the original Piano Row. For many years local piano rebuilder and dealer John J. Riley had a shop in Chinatown, which Philadelphians who grew up in the city may fondly remember. Philatuner Piano Works was approached by Mr. Riley in 2019, who was seeking to give away the remainder of his collection of parts and supplies accumulated from decades in business.

The fate of smaller firms is largely unknown today. Blasius & Sons left little trace in the Delaware Valley, and Albrecht’s few surviving instruments have become veritable relics, with one held in reserve in the instrument collection of the Smithsonian Institute.

Headline

Still, despite a century of decline, pianos remains popular among Philadelphians today. While new piano sales have declined significantly since the 1970s, the used piano market remains a thriving source for apartment and home dwellers eager to bring the presence and symbolism of a piano into their home. It is difficult to calculate how many pianos survive from earlier periods, but as the largest and most expensive household purchase apart from automobiles, pianos have persisted as a market force outside of the conventional consumer economy as owners regularly gift their instruments to second, third, and fourth homes, advertising their pianos for free to anyone willing to pay for the cost of moving.

With no innovations in the acoustic piano industry since the early 20th century, a used piano from 30 years ago is essentially the same as one made new today, albeit with lower manufacturing tolerances and parts worn from decades of use. For many aspiring piano owners, these instruments are enough to satisfy the urge of ownership.

Headline

From the time that piano design reached its zenith in the early 1900s, pianos have held a place in American culture that they have stubbornly resisted vacating. With the advent of player pianos around the turn of the 20th century, the piano likely had a cutting-edge cultural appeal similar to that of electric self-driving cars today. As purchasable symbols of the technological progress of the machine age, pianos at the time were icons of wealth and class status, mirroring the role that luxury tech brands would later play in the first decades of the 21st century.

As the piano industry traveled its long and steep decline, new piano manufacturing has all but disappeared in the United States. Piano rebuilding, its closest analogue, now remains the chief cultural expression for those who in another time would have set up their own piano making firms, like Albrecht or Loud Evenden did in Old City in the 1800s. For high-end brands like Steinway & Sons, rebuilt pianos compete with sales of new instruments, with price tags tens of thousands of dollars lower and the added perk of having a tangible material connection to the “golden age” of piano making.

Headline

It is doubtful that anyone making pianos in Philadelphia in the 1800s could have imagined that their instruments would still be in use over a century later, but it is also doubtful that these same makers would have bet against the piano’s cultural longevity. Early 20th century pianos of mature design from makers like Mason & Hamlin and Steinway & Sons will likely be restored and rebuilt for as long as pianos are played, mirroring how instruments like Stradivarius violins have come to occupy a vaunted place in world musical heritage.

While Philadelphia’s place in the history of piano making has long since come and gone, the industry’s impact on the city can still be seen to this day, and the pianos found in the city’s homes, churches, and concert halls remain a powerful reminder that some things are built to last, and that some things will endure.

Tom Rudnitsky is a pianist, composer and piano rebuilder, and the founder of Philatuner Piano Works, a restoration workshop located in the historic Bok Building in South Philadelphia.

Tom Rudnitsky is a pianist, composer and piano rebuilder, and the founder of Philatuner Piano Works, a restoration workshop located in the historic Bok Building in South Philadelphia.